William Bligh. Engraving by John Conde from a 1792 picture by John Russell.

Broken up following the American Revolution of 1775-83 was the profitable and long standing trade in which, among other things, Philadelphia, New York, and other North American ports sent grain and flour to feed the slaves in Jamaica, Barbados, and other sugar islands, getting in exchange sugar and rum. The British, at the close of the war, put an end to that arrangement, to the distress of the Americans and even more so to the sugar islands, where slave holders found it difficult to feed their slaves. Joseph Banks had been on Captain Cook’s 1768 to 1771 Endeavour Voyage to the Pacific and had seen the value of breadfruit as a highly productive food source. As Colonial administrators and plantation owners called for the introduction of this plant to the Caribbean Banks, who also had business interests in the West Indies, and in 1778 had become the President of the Royal Society, provided a cash bounty and gold medal for success in taking a thousand or so young breadfruit plants to provide a cheaper high energy alternative to grain to feed the West Indian slaves and lobbied his friends in government and the Admiralty to sponsor a British Naval expedition to Tahiti. He considered Bligh as the best person to head such a project since Bligh had experience in the Pacific, as Sailing Master on Cook’s third voyage on the Resolution, and following Cooks’ death in Hawaii in February 1779 had navigated HMS Resolution back to England. Being highly influential in Court circles and having access to the king, Banks had no difficulties in getting his desires realised.

On 23rd December 1787 His Majesty’s Armed Vessel Bounty proceeded to the South Pacific to fulfil this task. After trying unsuccessfully for a month to round Cape Horn, the Bounty was finally defeated by the notoriously stormy weather and forced to take the long way around the Cape of Good Hope. That delay resulted in Bligh arriving in Tahiti only in October 1788 and having to wait five months for the breadfruit plants to mature enough to be transported. Departing with over 1000 plants collected, potted, and transferred to the ship, in April 1789, within a month of leaving, many of the crew mutinied. Cast adrift in a lifeboat with 18 members of his crew, and with food sufficient only for a week, Bligh navigated through high seas and storms over a period of 48 days drawing on his memory of the few charts he had seen of the mostly uncharted waters. His completion of the 3,618-mile voyage to safety in Timor in June 1789 is still regarded as perhaps the most outstanding feat of seamanship and navigation ever conducted in a small boat. For comparison Shackleton’s epic journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia in April 1916 was 800 miles and took 15 days. The Bounty with the remaining nine mutineers led by Fletcher Christian, arrived at Pitcairn Island in January 1790. Bligh, on the Dutch East Indiaman Vlijt, returned via the Cape of Good Hope and Holland then on to England arriving in March 1790. In October he was court-martialed but exonerated.

In March 1791 Bligh was appointed to command a second expedition to take breadfruit from Tahiti to the West Indies. This time, the experiences of the first voyage, led to his ship HMS Providence, being better equipped and manned, it included a party of Marines and Providence was accompanied by HMS Assistant. The ships left Spithead on 3 August 1791 and arrived at Tahiti on 9 April 1792. They remained until July and left with over 2,600 breadfruit plants. They arrived at St Helena in December and deposited some of the plants, before continuing on to the West Indies.

A branch of the bread-fruit tree with fruit. Engraving by John Frederick Miller for inclusion within John Hawkesworth's account of the "Voyages in the Southern Hemisphere" London, 1773. National Library of Australia.

Bligh’s 10 day visit is described in “Captain Bligh’s Second Voyage to the South Sea”, Ida Lee, 1920

St. Helena was seen from the masthead at daylight on December 17th, 9 leagues distant. Early in the morning while the ships were on their way to the anchorage the second lieutenant was sent off in the launch to wait on the Governor. At 9.30 the vessels came abreast of the 4th Battery, where they were saluted with an equal number. An hour later after having spent ten weeks at sea, they anchored half a mile from the shore, St. James Church Tower and the Flag Staff both South by West.

“At noon after I anchored an officer was sent from the Governor, Lt. -Colonel Broke (sic) to welcome us. I landed at 1 o'clock when I was saluted with 13 guns, and the Governor received me. In my interview with him I informed him of my orders to give into his care 10 breadfruit plants, and one of every kind (of which I had five), as would secure to the island a lasting supply of this valuable fruit which our most gracious King had ordered to be planted there. Colonel Broke (sic) expressed great gratitude, and the principal plants were taken to a valley near his residence called Plantation House, and the rest to James's Valley. On the 23rd I saw the whole landed and planted; one plant was given to Major Robson, Lt. -Governor, and one to Mr. Rangham, the first in Council. I also left a quantity of mountain rice seed here. The Peeah (Sago) was the only plant that required a particular description. I therefore took our Otaheitan friends to the Governor's House where they made a pudding of the prepared part of its root, some of which I had brought from Otaheite." Writing of St. Helena, Captain Bligh says: “Few places look more unhealthy when sailing along its burnt-up cliffs huge masses of rock fit only to resist the sea, yet few places are more healthy. The inhabitants are not like other Europeans who live in the Torrid Zone, but have good constitutions the women being fair and pretty.

James Town, the capital, lies in a deep and narrow valley, and it is little more than one long street of houses; these are built after our English fashion, most of them having thatched roofs. Lodgings are scarce, so I was fortunate in finding rooms with Captain Statham in a well-regulated house at the common rate of twelve shillings a day. The Otaheitans were delighted with what they saw here, as Colonel Brooke showed them kind attention, had them to stay at his house, and gave them each a suit of red clothes." A letter from the Governor and Council of St. Helena was sent to Captain Bligh before he left conveying thanks for the gifts which the recipients declared "had impressed their minds with the warmest gratitude towards His Majesty for his goodness and attention for the welfare of his subjects"; while the sight of the ships " had raised in them an inexpressible degree of wonder and delight to contemplate a floating garden transported in luxuriance from one extremity of the world to the other " All needful refreshment was taken on board, and the ships left St. Helena on December 27th, receiving the salute from the battery on Ladder Hill as they sailed out of the harbour.

Janisch’s Extracts From the St Helena Records gives different dates.

1792 Dec. 24.—Captain Bligh at St. Helena in H.M.S. Providence with Bread fruit trees, Mango and various other plants enumerated.

1792 Dec. 29.—Capt. Bligh sent on shore to us a variety of Trees and Plants the productions of the South Seas and the Island of Timor.

Arriving at St Vincent on 23rd January 1793 they continued to Jamaica where they remained until June. After a short delay caused by the outbreak of war with France, they returned to Britain on 7th August and were able to send a cargo of plants to Kew Gardens. However, Bligh returned home to a tarnished reputation since, during his absence, the trial of the Bounty mutineers had taken place and examples of his hot temper had been circulated. He was placed on half pay and remained unemployed for eighteen months. Banks remained a faithful patron of Bligh’s throughout the Captain’s career and was instrumental in arranging for Bligh’s appointment as Governor of New South Wales in 1805.

Alas, bread-fruit, which many believed would be an inexpensive miracle food to feed slaves in the Caribbean, turned out to be a total disaster in that regard. Nobody would eat it because they didn't like its taste and even the plants left on St Helena died from lack of attention. Although Bligh won the Royal Society medal for his efforts, his two trips to the South Pacific had proven economic failures.

As reported in The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge 1832 article “The Bread Fruit” “After all the peril, hardship, and expense thus incurred, the bread-fruit tree has not, hitherto at least, answered the expectations that were entertained. The banana is more easily and cheaply cultivated, comes into bearing much sooner after being planted, bears more abundantly, and is better relished by the negroes. The mode of propagating the bread-fruit is not, indeed, difficult; for the planter has only to lay bare one of the roots, and mound it with a spade, and in a short space a shoot comes up, which is soon fit for removal. Europeans are much fonder of the bread-fruit than negroes. They consider it as a sort of dainty, and use it either as bread or in puddings. When roasted in the oven, the taste of it resembles that of a potato, but it is not so mealy as a good one.”

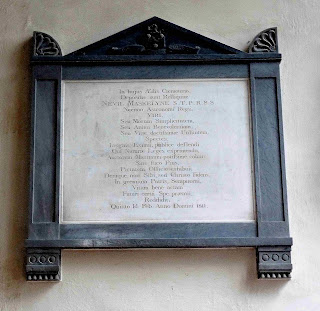

Bligh died in London in December 1817 and is buried in St Mary's Churchyard Lambeth where his tomb is topped by a breadfruit. Born on 9th September 1754 Bligh was 63 when he died and not 64 as inscribed on his tomb.

SACRED

TO THE MEMORY OF

WILLIAM BLIGH ESQUIRE F.R.S.

VICE ADMIRAL OF THE BLUE

THE CELEBRATED NAVIGATOR

WHO FIRST TRANSPLANTED THE BREAD FUIT TREE

FROM OTAHEITE TO THE WEST INDIES

BRAVELY FOUGHT THE BATTLES OF HIS COUNTRY

AND DIED BELOVED, RESPECTED AND LAMENTED

ON THE 7TH DAY OF DECEMBER 1817,

AGED 64